You already know what customer lifetime value is. You're here because you want to know if yours is any good.

The problem?

Everyone throws around different numbers.

You'll see one article say $200 is solid, another claiming anything under $500 means you're screwed.

Meanwhile, you're sitting there with your actual data wondering if you should panic or pop champagne.

The truth behind average CLV is that it varies wildly depending on what you sell, who you sell to, and how you sell it.

A skincare brand and a furniture store aren't even playing the same game.

So let's cut through the noise and look at what the numbers actually look like across different types of ecommerce brands—and more importantly, figure out where you stand.

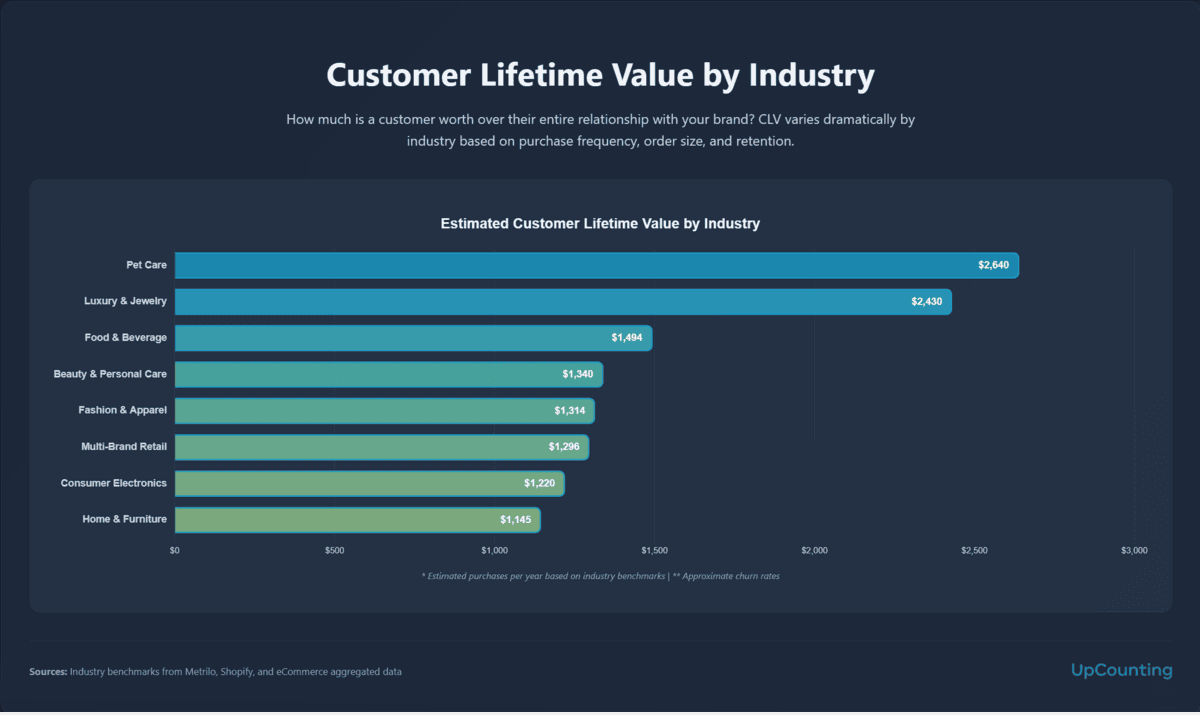

Average Customer Lifetime Value for eCommerce

The average CLV across most eCommerce industries is $1,609*.

But that’s not the full story.

We don't have perfect data on actual CLV across industries.

What we do have is average order value and annual churn rates.

So we're going to make some educated guesses and show you exactly how we got there.

Our formula: CLV = AOV × Purchase Frequency per Year × Customer Lifespan (years)

Our assumptions:

- We're using a 3-5 year business planning window for customer lifespan (conservative, realistic for forecasting)

- The theoretical maximum is much longer—people buy furniture for 20+ years, electronics for their entire adult life—but that's harder to model and predict

- Purchase frequency is based on product consumption cycles and category behavior

- We're calculating for customers who DO return (the ones who survive that brutal first-year churn)

Full transparency: these are estimates.

Your actual numbers will vary based on your retention efforts, product quality, pricing, and a dozen other factors.

Estimated Customer Lifetime Value by eCommerce Industry

*For customers who return after first purchase **Estimated based on similar categories

Luxury & Jewelry ($2,430 estimated CLV)

This one surprises people.

Yes, the churn is high—roughly 75% don't come back within a year. But the ones who do?

They're buying gifts for anniversaries, birthdays, special occasions.

Maybe 1-2 purchases per year, but at $324 a pop, and they stick around for years.

Someone who buys an engagement ring from you might come back for wedding bands, anniversary gifts, birthday presents for their spouse.

Over a 5-year window, that's serious money.

Theoretical maximum? Could be 20-30 years of gifting occasions.

Home & Furniture ($1,145 estimated CLV)

People aren't buying couches every month.

Maybe once a year on average—a new chair, some shelves, a table, gradually furnishing or refreshing spaces. 75% churn makes sense; lots of one-time project buyers.

But the ones who come back are setting up homes, moving, redecorating over years.

Conservative estimate at 5 years and 1 purchase annually gets you to $1,145.

Theoretical maximum? 20+ years. Think about how long you've been buying furniture.

Consumer Electronics ($1,220 estimated CLV)

High AOV, high churn (82%). Most people buy a phone case or laptop and you never see them again.

But the ones who return are in your ecosystem—buying accessories, upgrades, replacements every year or so.

Over 5 years at roughly 1 purchase per year, you're looking at $1,220.

Theoretical maximum? 30-40 years. People buy electronics their entire adult lives.

Fashion & Apparel ($1,314 estimated CLV)

Right at the average AOV ($146), high churn (71%). But fashion is seasonal.

The customers who return are coming back 3-4 times per year—new season, new needs. We're being conservative at 3 purchases per year over 3 years.

That gets you to $1,314.

Theoretical maximum? 10-20 years if you keep them engaged.

Multi-Brand Retail ($1,296 estimated CLV)

These are the general stores of ecommerce.

Lower AOV ($108), but customers come back more frequently because you carry different things they need.

Estimating 4 purchases per year over 3 years gets you close to $1,300.

Theoretical maximum? Could be 10+ years of regular shopping.

Food & Beverage ($1,494 estimated CLV)

AOV is low ($83), but here's the thing about food: people eat it. Then they need more.

The 64% churn is still brutal—lots of one-time curiosity purchases or gifts.

But customers who come back are buying 6+ times per year. Specialty foods, snacks, beverages people reorder.

Over 3 years, that's nearly $1,500.

Theoretical maximum? 15-20 years if you've got products they love.

Beauty & Personal Care ($1,340 estimated CLV)

Lowest AOV at $67, but products run out.

The 62% churn (lowest in our data) tells you something—this category has the best shot at repeat purchases.

People find products they like and stick with them.

We're estimating 5 purchases per year over 4 years. Shampoo runs out, skincare runs out, they come back.

That's $1,340 in CLV.

Theoretical maximum? 10-20 years. People use beauty products their entire adult lives.

Pet Care ($2,640 estimated CLV)

Here's the winner. Lowest AOV ($66), but the highest estimated CLV.

Why? Because pets eat. Every. Single. Month.

The 70% annual churn seems high, but think about it—lots of people try a product once, their pet doesn't like it, they move on.

But the ones who find food their pet actually eats? They're buying 10-12 times per year, every year, for the life of that pet.

Conservative estimate: 10 purchases per year over 4 years = $2,640.

Theoretical maximum? 15+ years across multiple pets.

Why We Use 3-5 Years (When the Theoretical Maximum Is a Lifetime)

Let's be clear about something: the theoretical maximum for most of these categories isn't 15 or 20 years. It's 50+ years.

People don't stop eating after 20 years.

They don't stop wearing clothes.

They don't stop needing furniture or using beauty products or buying electronics.

If you're in food and beverage, your customer could theoretically keep buying from you for their entire adult life—40, 50, 60 years.

Same with beauty, fashion, pet care (across multiple pets), home goods, all of it.

So why are we using a 3-5 year window?

Because that's realistic for business planning, not because customers stop needing your products.

The theoretical maximum shows you what's possible if everything goes perfectly.

The 3-5 year window shows you what you can actually count on when making business decisions.

Here's the thing: over a 50-year timeframe, a million things will happen.

Your customer's needs will change. Their income will change. Their taste will evolve.

Competitors will launch better products. New categories will emerge. Trends will shift.

And yes, you'll probably fumble the ball somewhere along the way.

Think about your own buying habits. How many brands have you been loyal to for 20+ years? Maybe a couple.

How many have you cycled through in categories you buy from constantly? Dozens, probably hundreds.

It's not that you stopped needing coffee, or skincare, or pet food.

You just stopped buying it from that specific brand.

Maybe they raised prices. Maybe their quality slipped.

Maybe you just got bored and wanted to try something new. Maybe a better option showed up.

The category lifespan is forever. The brand lifespan with any individual customer is fragile.

Think about Nokia.

People didn't stop buying phones.

They stopped buying Nokia phones.

The theoretical maximum was real—people are still buying phones every 2-3 years. Nokia just isn't in the equation anymore.

So the 3-5 year window isn't pessimistic. It's practical.

It's a timeframe where:

- You can reasonably forecast your business performance

- Market conditions won't have completely transformed

- You have some control over the customer relationship

- Your assumptions about product-market fit still hold

Beyond that? You're guessing.

Maybe you'll keep that customer for 10 years, 20 years, their whole life. That would be incredible.

But you can't plan around it, and you definitely can't take it to investors or use it to make strategic decisions.

Use the 3-5 year window for your models and your planning.

But remember the theoretical maximum exists.

It reminds you what's at stake if you get retention right—and what you're leaving on the table every time a customer churns.

Because they're not leaving the category. They're just leaving you.

What Your Accountant Wishes You Knew About CLV

Most articles about improving CLV will tell you to offer discounts, create bundles, launch a loyalty program, send more emails. And sure, those tactics can work.

But here's what nobody mentions: they only work if the math actually works.

You can't discount your way to profitability. You can't bundle yourself into the ground. And you definitely can't improve CLV by spending more to keep customers than those customers are worth.

This is where most ecommerce brands screw up. They focus on increasing CLV without understanding if they can actually afford to do it.

The Numbers That Actually Matter

Before you do anything to "improve" your CLV, you need to know three things:

1. Your Contribution Margin

This isn't revenue. This isn't even gross profit. Contribution margin is what's left after you account for:

- Cost of goods sold

- Payment processing fees

- Shipping costs (what you actually pay, not what the customer pays)

- Picking and packing

- Returns and refunds

If your AOV is $100 but your contribution margin is $30, that's your actual starting point. Every discount, every "free shipping" offer, every bundle deal comes out of that $30, not the $100.

We see brands celebrating a $150 CLV without realizing their contribution margin per order is $35 and they're spending $60 to acquire each customer.

Congratulations, you've built a machine that loses money at scale.

2. Your Customer Acquisition Cost (CAC)

Not your Facebook CPA. Not your "blended" number that makes you feel better. Your actual CAC—total marketing and sales spend divided by new customers acquired.

This includes:

- Paid ads (all channels)

- Agency fees

- Creative production

- Influencer payments

- Affiliate commissions

- Any other money you spend to get customers in the door

The rule of thumb everyone throws around is that CLV should be 3x CAC. That's fine as a starting point.

But what actually matters is: can you afford to acquire customers at your current CAC and still make money after accounting for contribution margin?

3. Your MER (Marketing Efficiency Ratio, or Blended ROAS)

Media Efficiency Ratio is total revenue divided by total marketing spend. It's the number that tells you if your entire marketing engine is efficient, not just individual campaigns.

You might have a Facebook campaign running at 4x ROAS while your Google campaigns run at 2x and your email marketing runs at 10x.

Your MER tells you what's actually happening when you blend it all together.

If your MER is 3.5x and your contribution margin is 35%, you're spending roughly 28% of revenue on marketing.

That leaves you 7% in contribution margin before operational expenses. Better hope your ops are tight.

Why This Matters for CLV

Let's say you want to improve CLV by launching a loyalty program that gives customers 10% off their third purchase.

Sounds reasonable, right? You're incentivizing repeat purchases, building loyalty, all that good stuff.

But run the math:

- Your AOV is $100

- Your contribution margin is $30 (30%)

- Customer buys three times

- First two purchases: $30 contribution margin each = $60

- Third purchase with 10% off: AOV drops to $90, but your costs stay the same, so contribution margin drops to $20

- Total contribution margin: $80 across three purchases

Now factor in your CAC of $50.

You just made $30 per customer after three purchases. That's your actual profit before operational overhead.

Is it worth it? Maybe. But you better know that number before you launch the program, not after.

The Real Way to Improve CLV

Stop thinking tactics. Start thinking economics.

Can you improve your contribution margin by:

- Negotiating better COGS

- Raising prices (yes, actually)

- Reducing shipping costs

- Decreasing return rates

- Improving your product mix toward higher-margin items

Can you decrease your CAC by:

- Improving conversion rates (same ad spend, more customers)

- Better targeting (fewer wasted impressions)

- Stronger creative (higher CTR, lower CPMs)

- Building organic channels that don't require paid acquisition

Can you increase purchase frequency without torching your margins:

- Post-purchase experience that makes people want to come back

- Product quality that creates natural replenishment cycles

- Content and community that keeps you top of mind

The tactics everyone recommends—discounts, bundles, loyalty programs—can absolutely work. But only if you've done the math first and know you can afford them.

We've seen too many brands "improve" their CLV from $150 to $200 while their actual profit per customer went from $20 to $5.

Revenue looks better, the metrics look better, the dashboards are green. And the business is dying.

Know your numbers. Contribution margin, CAC, MER. Then decide how to improve CLV in a way that actually makes you more money, not just generates more revenue.

If you're tired of looking at dashboards that show growth while your bank account tells a different story, it's time to get serious about your books.

We help ecommerce brands understand their actual unit economics—contribution margin, true CAC, customer profitability, the numbers that determine whether you have a business or an expensive hobby.

Because knowing your average CLV is worthless if you don't know whether you can afford to achieve it.

Schedule a free clarity call and we'll show you exactly where your money is going—and where it should be going instead.

.jpg)

.jpg)