Imagine your shipment from China is on a truck heading from the Port of Long Beach to your 3PL in Ontario.

You've got $47,000 worth of product in there—already paid for, already cleared customs.

Then Dom Toretto and the family show up, because apparently in addition to stealing ATMs and pulling bank vaults through the streets of Rio, they've decided your electrolyte powder is worth a precision highway heist.

The truck is gone. Your inventory is gone.

So here's the question: Do you book that loss to Cost of Goods Sold, or do you put it in SG&A as an operating expense?

If you had to pause and think about it, you're not alone.

And if you don't know the answer to the dramatic scenario, what about the mundane ones that happen every single day?

Your manufacturer shorts you 2,000 units but charges you for the full order.

Your freight forwarder bills you $800 instead of the $600 you accrued—but you already sold half the inventory.

Your 3PL receives 19,900 units instead of the 20,000 on the packing slip, and no one tells you for three months.

Where does all of that show up in your books? When does it hit your P&L?

How does it flow between your IMS, your accounting software, and your 3PL's dashboard?

There's a whole journey—deposits, shipments, customs, freight forwarders, co-manufacturers, multiple warehouses—and every single one of those steps needs to show up somewhere in your books.

When it doesn't? That's when cash disappears into the ether of "mysterious inventory."

That's when your COGS is wrong, your margins are wrong, and you're making decisions based on numbers that don't reflect reality.

Most brands suffer from not understanding how inventory actually flows through their systems.

Not because they're careless, but because almost nobody's supply chain looks the same, and the connective tissue between "I paid for this" and "I can sell this" is rarely explained clearly.

So let's walk through it.

These are the nine places where things typically fall apart—the gaps between systems, the missed steps, the "close enough" shortcuts that compound into real problems.

Not to point fingers, but to show you what's actually happening behind the scenes so the numbers start making sense.

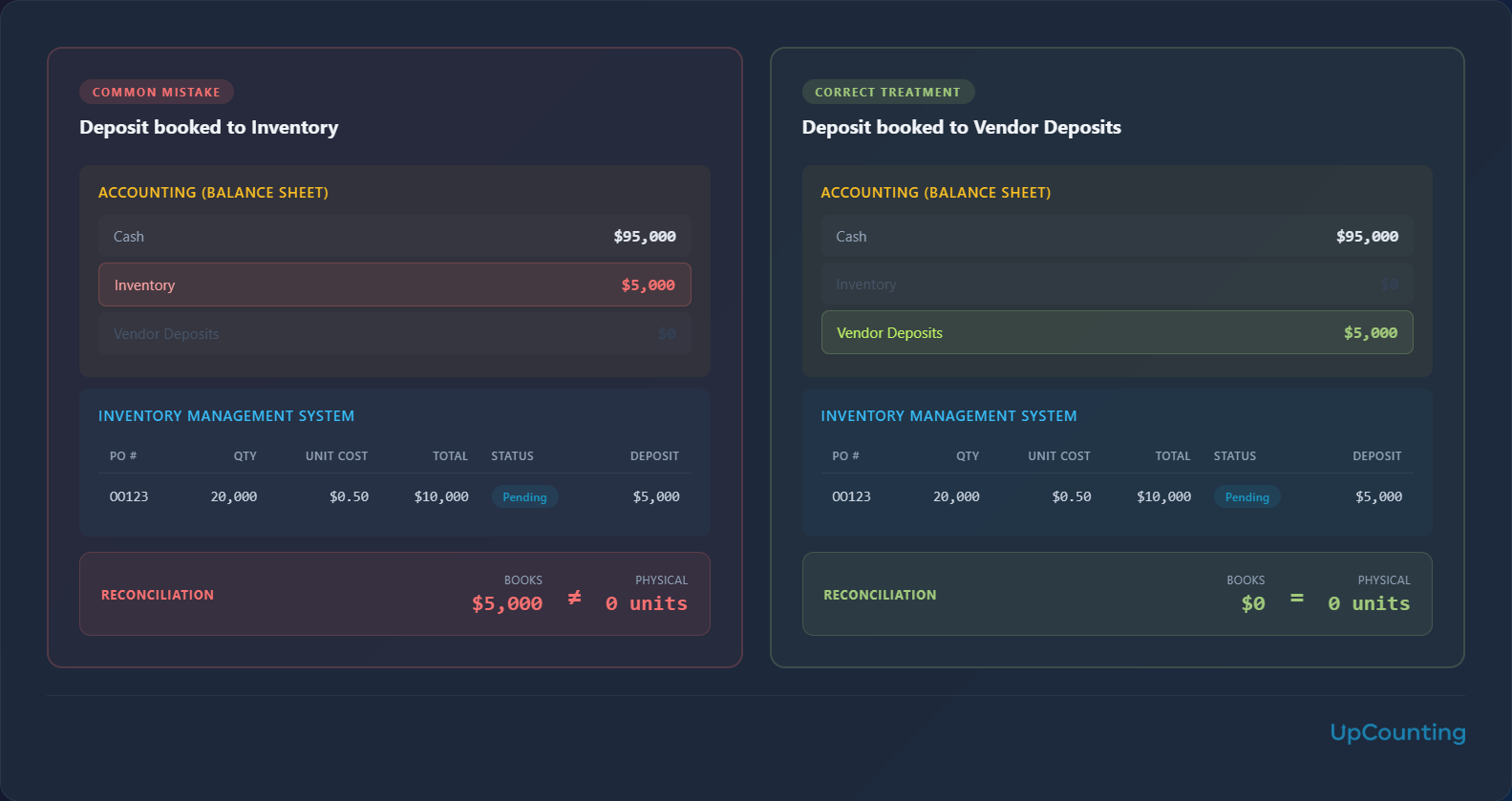

Mistake #1: Booking Supplier Deposits Directly to Inventory

You place a purchase order with your packaging supplier for 20,000 units at $0.50 each. Total order: $10,000.

They send you a proforma invoice asking for a 50% deposit before they start the manufacturing run. Standard practice. You wire them $5,000.

Now, where does that $5,000 go in QuickBooks?

A lot of brands book it straight to their Inventory account. It makes intuitive sense, right? You're paying for inventory. It's going to become inventory. So... inventory.

Except here's what just happened: Your accounting software now shows you have $5,000 of inventory sitting on your balance sheet.

But your IMS—if you're even tracking this—shows zero units.

Your 3PL has zero units. Your co-manufacturer has zero units. Because there is no physical inventory yet. They haven't even started making it.

So now you're trying to reconcile, and the numbers don't match.

Your accounting software says you have $5,000 in inventory. Your IMS says you have $0.

Which system is lying?

Neither. They're both right. You just put the money in the wrong bucket.

What should happen instead:

When you pay a deposit, you're not buying inventory—you're creating a future claim to inventory. It's an asset, but it's not inventory yet.

The $5,000 should go to a Supplier Deposits account (still an asset on your balance sheet, just a different line). This way:

- Your cash balance drops by $5,000 ✓

- Your Supplier Deposits balance increases by $5,000 ✓

- Your Inventory balance stays at $0 ✓

- Your IMS shows 0 units ✓

Everything matches.

Later, when the goods actually ship and you pay the remaining $5,000, that's when both amounts move from Supplier Deposits into Goods in Transit (which we'll get to in Mistake #2).

And when the goods are physically received at your warehouse, they move from Goods in Transit to Inventory.

Why this matters:

If you're booking deposits directly to inventory, you're overstating your inventory balance before you actually have anything to sell.

And if you're trying to reconcile your inventory value between your accounting software and your IMS—which you should be doing regularly—you're going to be chasing phantom discrepancies that only exist because the deposit is sitting in the wrong account.

It's a small distinction, but it's the foundation for everything that comes after. Get this wrong, and every subsequent step compounds the error.

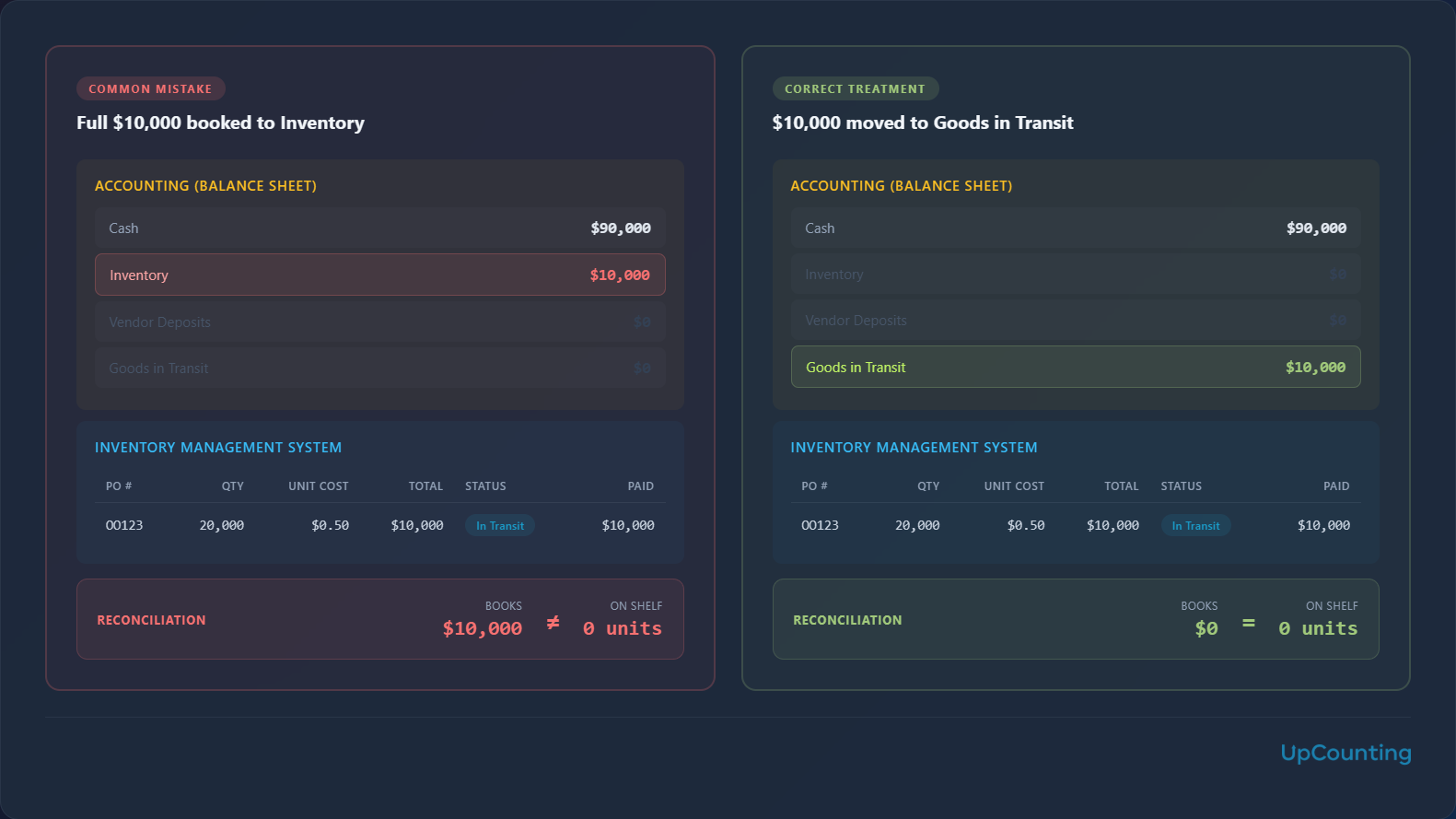

Mistake #2: Treating Pre-Shipment Payments as Received Inventory

Fast forward two weeks.

Your packaging supplier finishes the manufacturing run and sends you an invoice for the remaining balance—another $5,000, due on receipt.

You pay it. They load the 20,000 units into a container and ship it out.

The goods are now on a boat somewhere between Shenzhen and Long Beach.

Technically, they belong to you. Ownership typically transfers once the shipment leaves the manufacturer (depending on your Incoterms, but let's assume FOB for simplicity).

So here's the question: Is this inventory?

Legally? Yes. You own it.

Physically? No. You can't touch it. You can't sell it.

It's not at your 3PL. It's not at your co-manufacturer.

It's on a container ship somewhere in the Pacific.

Yet a lot of brands will take that $5,000 final payment, combine it with the $5,000 deposit, and book the full $10,000 straight to their Inventory account.

Now you've got $10,000 of "inventory" in QuickBooks. But when you pull up your 3PL's dashboard, it shows zero units.

When you check your IMS, it shows... zero units. Because the goods haven't been received anywhere yet.

So you're sitting there looking at a $10,000 discrepancy thinking, "Did we lose a shipment? Did the 3PL forget to log it? Is my IMS broken?"

No. The inventory is just in the wrong status.

What should happen instead:

When the shipment leaves the manufacturer, both the deposit ($5,000) and the final payment ($5,000) should move into a Goods in Transit account.

This is still an asset. It's still inventory you own. But it's inventory that's in transit—not sitting on a shelf ready to be picked and shipped to customers.

In your IMS, those 20,000 units should also be categorized as "Goods in Transit." Not at any specific warehouse location. Just... in limbo. On the move.

So now:

- Your Supplier Deposits account goes from $5,000 to $0 ✓

- Your Goods in Transit account shows $10,000 ✓

- Your IMS shows 20,000 units in transit status ✓

- Your 3PL's dashboard shows 0 units (which is correct—they haven't received it yet) ✓

Everything syncs up.

Later, when the container actually arrives at your 3PL and they receive it, that's when the $10,000 moves from Goods in Transit to your actual Inventory account.

And that's when your IMS changes the status from "in transit" to "on hand" at the 3PL location.

Why this matters:

If you're booking in-transit inventory as received inventory, you're constantly going to have discrepancies between what your accounting software says you have and what your 3PL actually has on their shelves.

And when you're trying to forecast inventory levels or decide whether to place another order, you need to know the difference between "I own this, but it's still 30 days away on a boat" and "I own this, and it's sitting in my warehouse ready to ship."

One is available for sale. The other isn't. The distinction matters.

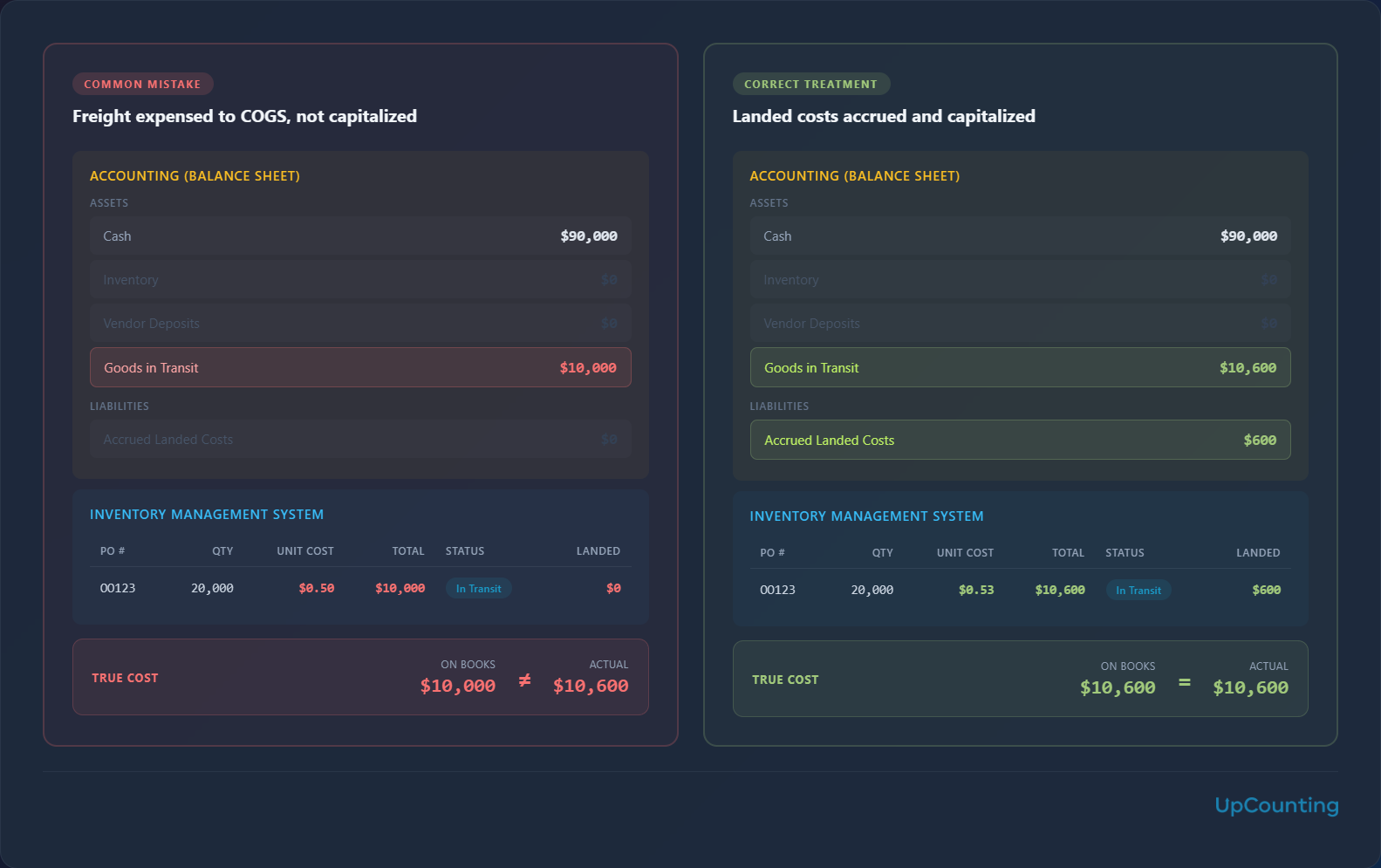

Mistake #3: Not Capitalizing Landed Costs to Your Inventory

Your container is crossing the Pacific.

It arrives in Long Beach. Customs clears it. A freight forwarder picks it up and delivers it to your 3PL.

All of that costs money. Customs duties. Import fees. Freight forwarding. Drayage. Let's say it's $600 total.

Here's the thing: You don't usually get these bills right away.

The freight forwarder might not invoice you until two weeks after delivery. Customs might bill you a month later. But the costs have already been incurred.

So when your inventory arrives at the warehouse, what's the actual cost per unit?

Most brands will say it's $0.50—the amount they paid the supplier. But that's not the true cost.

The true cost is $0.50 plus the $600 in landed costs, spread across 20,000 units. That's $0.53 per unit.

Yet a lot of brands won't capitalize those landed costs to their inventory.

They'll just wait until the freight bill comes in, and when it does, they'll expense it directly to COGS or book it as a miscellaneous shipping expense.

Which sounds fine until you realize: you're now undervaluing your inventory, and when you sell it, your COGS is going to be wrong.

What should happen instead:

Even if you haven't received the freight bill yet, you should estimate the landed costs and accrue them as a liability.

Let's say you estimate $600 for customs and freight. Here's how that should flow:

In your IMS:

- Capitalize the $600 estimate to the inventory value

- Your 20,000 units now cost $10,600 total (instead of $10,000)

- Your unit cost increases from $0.50 to $0.53

In your accounting software:

- You haven't paid the bill yet, so your cash hasn't moved

- Create an Accrued Landed Costs liability for $600

- Add $600 to your Goods in Transit account (now $10,600)

Now both systems match.

The inventory is valued at its true cost, which includes what it cost to get the goods to your warehouse—not just what you paid the supplier.

Later, when the freight forwarder's invoice actually arrives, you reverse the accrual and book the actual amount to Accounts Payable.

If the real bill is $800 instead of $600, you adjust the inventory value accordingly (which we'll cover in Mistake #5).

Why this matters:

If you're not capitalizing landed costs, your inventory is undervalued on your balance sheet.

But more importantly, when you sell that inventory, your COGS is going to be understated. Which means your gross margins are going to look better than they actually are.

So you're looking at your P&L thinking you're hitting 60% margins, when in reality you're at 55% because you forgot to factor in the $600 it cost to get the goods from Shenzhen to California.

And if you're making pricing decisions, inventory purchasing decisions, or marketing budget decisions based on those inflated margins? You're operating on bad data.

The $600 doesn't disappear just because the invoice is delayed. It's a real cost, and it needs to be reflected in your inventory value from the moment the goods arrive.

Mistake #4: Not Properly Recording the Receipt of Goods Into Your Warehouse

The container arrives. Your 3PL unloads it, counts it, puts it on the shelves. The physical inventory is now sitting in your warehouse, ready to pick and ship.

So in your systems... what changes?

A surprising number of brands either don't update anything at this point, or update the wrong thing. The goods were already showing up somewhere in their books (Goods in Transit, if they followed Mistakes #2 and #3 correctly), so they figure the hard part is done.

But this step matters, and it matters in two specific ways.

In Your IMS: Status and Location

When your 3PL receives the goods, two things need to update in your IMS:

- Status changes from "In Transit" to "Received" (or "On Hand")

- Location changes from a generic in-transit bucket to the specific warehouse location

This sounds obvious. But if you're not updating the location, you'll have inventory that technically shows as "received" but isn't assigned anywhere. When you try to create a fulfillment order and your system asks which location to pull from, it either errors out or pulls from nothing.

And if you're managing multiple locations—a 3PL, a co-manufacturer's facility, an Amazon FBA warehouse—and everything is lumped together without location tags, you've lost visibility into what's actually where.

In Your Accounting Software: Moving to the Right Account

This is where a lot of brands make a subtle but important error.

When the goods move from Goods in Transit to your actual inventory balance, they can't just go to a generic "Inventory" account. They need to go to the right inventory account based on what you actually received.

- Raw materials (packaging, labels, ingredients) → Raw Materials inventory account

- Finished goods ready to sell → Finished Goods inventory account

Why does this matter? Because later, when you're manufacturing (converting raw materials into finished goods), you need to be able to reduce your Raw Materials balance and increase your Finished Goods balance accurately. If everything is sitting in one undifferentiated "Inventory" account, that movement becomes invisible and untrackable.

So in your accounting software, when the 20,000 units of packaging are received at your 3PL:

- Goods in Transit: $10,600 → $0

- Raw Materials Inventory: $0 → $10,600

Same total assets on your balance sheet. Just in the right bucket.

Why this matters:

If you skip this step or use a catch-all inventory account, you'll have a clean-looking balance sheet that tells you nothing useful. You won't know how much of your inventory is raw materials waiting to be manufactured versus finished goods ready to sell.

And when you eventually do start manufacturing and try to track the cost of goods produced, you'll be doing it against a single opaque inventory balance instead of clearly defined inputs and outputs.

The receipt step is the moment inventory stops being "something I'm waiting for" and becomes "something I can actually use." Your systems should reflect that clearly.

Mistake #5: Skipping the Three-Way Match

Your 20,000 units arrive at the 3PL. They unload the container, scan everything in, and send you a receiving report. A few days later, your supplier sends you the final invoice.

Here's the question: Do the numbers match?

You ordered 20,000 units. Your 3PL received... how many? Your supplier is billing you for... how many?

If you're not checking, you don't know. And if you don't know, you might be paying for inventory you didn't receive. Or you might have received inventory you're not paying for (which sounds good until your supplier figures it out six months later and sends you a surprise invoice).

This is where the three-way match comes in. It's a simple process:

- Pull up your Purchase Order (what you ordered)

- Pull up your Goods Received Document (what your 3PL actually took in)

- Pull up your Supplier Invoice (what they're charging you for)

If all three say 20,000 units at $0.50 each? Great. You're good. Move on.

But if they don't match? That's when things get interesting.

Scenario 1: The Short Ship

Your PO says 20,000 units. Your supplier's invoice says 15,000 units. Your 3PL received 15,000 units.

They couldn't fulfill the full order. It happens. At least you're only being charged for what you got. But now you need to adjust your IMS to reflect 15,000 units instead of 20,000. And if you were counting on that full shipment for your inventory forecast, you're short 5,000 units.

Good to know now rather than three months from now when you're out of stock.

Scenario 2: The Overcharge

Your PO says 20,000 units. Your 3PL received 18,000 units. Your supplier's invoice says 20,000 units.

Wait. They're charging you for 20,000, but you only got 18,000?

If you're not doing a three-way match, you just pay the invoice. You're out $1,000 for inventory you don't have. Your IMS shows 18,000 units. Your accounting shows you paid for 20,000. The numbers don't reconcile, and you can't figure out why.

But if you are doing a three-way match, you catch this immediately. You reach out to the supplier, they adjust the invoice to 18,000 units, and you don't pay for 2,000 units you never received.

Scenario 3: The Surprise Bonus

Your PO says 20,000 units. Your 3PL received 22,000 units. Your supplier's invoice says 20,000 units.

You got 2,000 extra units for free. Technically.

Do you tell them? That's your call. But if you don't tell them and don't adjust your IMS, here's what happens:

- Your accounting shows you paid for 20,000 units at $0.50 = $10,000

- Your IMS should show 22,000 units

- But if you didn't update it, your IMS still shows 20,000 units

- So now you have 2,000 "ghost units" that exist physically but not in your system

Later, when you do a physical count, you're going to have a 2,000-unit discrepancy and no idea where it came from.

Scenario 4: The Damaged Goods

Your PO says 20,000 units. Your supplier's invoice says 20,000 units. Your 3PL received 20,000 units... but 100 of them are damaged.

If your 3PL catches this during receiving (and tells you), you need to adjust your IMS to show 19,900 units instead of 20,000. You also need to reduce your inventory value by $53 (100 units × $0.53) and push that to a COGS account called Shrinkage.

If the damage is substantial, you might dispute it with the supplier or file an insurance claim. But if it's a small amount—100 units out of 20,000—it's usually just the cost of doing business.

The key is knowing about it so you can adjust your numbers accordingly.

Why this matters:

Without a three-way match, you have no way of catching these discrepancies. You're just blindly paying invoices and assuming everything matches.

And maybe it does. But if it doesn't, you're either:

- Paying for inventory you don't have

- Receiving inventory you're not accounting for

- Operating with inaccurate inventory counts

All of which leads to bad data, bad decisions, and cash quietly leaking out of your business without anyone noticing.

Mistake #6: Mishandling Freight Bill Adjustments After You've Sold Inventory

Remember in Mistake #3 when you estimated $600 for freight and customs costs and accrued it as a liability?

Well, two months later, the freight forwarder's invoice finally arrives. And it's not $600. It's $800.

You were off by $200. It happens. Estimates are estimates.

Now you need to adjust your books to reflect the actual cost. Easy enough, right?

If all the inventory is still on hand, yes. Super easy.

You update your IMS from $600 to $800 in landed costs. Your unit cost goes from $0.53 to $0.54 (one cent higher). Your inventory value increases by $200. You reverse the $600 accrual and book $800 to Accounts Payable. Done.

But here's the problem: It's been two months. You've been selling this inventory the whole time.

Let's say you've sold half of it. You have 10,000 units left on hand, and the other 10,000 are already gone—sold to customers, shipped, invoiced, COGS recorded.

So now what?

The Wrong Way (But Tempting)

Option 1: Just update the remaining inventory by the full $200.

This makes your IMS match your accounting software. But now you've overcorrected. You're putting the entire $200 adjustment onto the 10,000 units you still have, when really that $200 should have been spread across all 20,000 units—including the 10,000 you already sold.

Your remaining inventory is now overvalued, and your historical COGS for the units you already sold is understated.

Option 2: Go back and adjust the COGS for the months when you sold the first 10,000 units.

Technically accurate. But now you're reopening closed months, restating historical financials, and probably confusing the hell out of anyone looking at your P&L trends.

Most accountants (and most business owners) don't want to do this.

The Right Way (Splitting the Adjustment)

Here's what should actually happen:

You had $600 accrued across 20,000 units. That's $0.03 per unit.

You've sold 10,000 units, so $300 of that accrual has already flowed through COGS. The other $300 is still sitting with the remaining 10,000 units on hand.

The actual bill is $800. That's $0.04 per unit across 20,000 units.

So:

- The 10,000 units you sold should have been charged $400 in freight costs (but were only charged $300)

- The 10,000 units you still have should be carrying $400 in freight costs (but are only carrying $300)

Here's the adjustment:

- Increase the remaining inventory by $100 (from $300 to $400 in freight allocation)

- Push the other $100 to COGS as a "catch-up" adjustment

Your IMS now shows 10,000 units at $0.54 per unit instead of $0.53. That extra $100 is reflected in your inventory value.

And the other $100 goes to COGS this month as a variance or adjustment line, catching up for the units you already sold in prior months at slightly understated COGS.

Your accounting software now shows:

- $400 allocated to the inventory you still have ✓

- $400 that went through COGS (half as catch-up, half from future sales) ✓

- Total $800 matches the actual freight bill ✓

Why This Matters

This scenario happens constantly. Freight bills are always delayed. Inventory is always moving. You're always making estimates that turn out to be slightly off.

If you're not splitting the adjustment between what's on hand and what's already been sold, you're either:

- Overstating the value of your remaining inventory

- Understating your COGS

- Creating reconciliation headaches that compound every time you make an adjustment

And if you're doing this wrong across multiple shipments, multiple bills, and multiple adjustments? The errors stack up fast.

This is one of the most common places where brands lose track of their true inventory costs. Not because they're careless, but because the mechanics of the adjustment aren't obvious, and most people just book the freight bill to whatever feels easiest in the moment.

Mistake #7: Not Accounting for Co-Manufacturing Costs Properly (GRNI)

Let's say you're not just importing finished goods. You're working with a co-manufacturer.

Your packaging arrives at their facility (20,000 units at $0.53 each = $10,600). Your labels arrive (15,000 units at $0.20 each = $3,000). Your bulk ingredient powder arrives (80 kg at $35/kg = $2,800).

You place an order with the co-manufacturer: "Produce 5,000 units of our Elite Pre-Workout."

They take your raw materials, add their own ingredients, do the mixing and filling, and three weeks later they ship you 5,000 finished units ready to sell.

Here's the question: What does each finished unit cost?

It's not just what you paid the co-manufacturer. It's:

- The packaging you provided ($0.53 per unit)

- The labels you provided ($0.20 per unit)

- The ingredient powder you provided (~$0.42 per unit)

- The co-manufacturer's ingredients and labor (let's say $6.60 per unit)

Total cost per unit: $7.75

But here's where it gets messy.

The Problem: Invoices Arrive Late (Again)

Your co-manufacturer ships the 5,000 finished units. You receive them at your 3PL. You start selling them.

But the co-manufacturer's invoice doesn't arrive for another two weeks. So you don't actually know what they're going to charge you yet.

If you wait until the invoice arrives to record anything, here's what happens:

In your IMS:

- Your raw materials haven't been reduced (you still show 20,000 packaging units, 15,000 labels, 80 kg of powder)

- Your finished goods show 5,000 units... but at what cost?

- You've already sold 1,000 of them. What COGS did you record?

In your accounting software:

- Your Raw Materials inventory balance is too high (you still have all of it on the books, even though 5,000 units' worth was consumed)

- Your Finished Goods inventory balance is... what? Zero? Too low? Totally wrong?

Your systems are out of sync, and you have no idea what your actual margins are on the products you're selling.

The Right Way: Estimate and Use GRNI

Just like with freight costs, you need to estimate the co-manufacturer's costs and book them before the invoice arrives.

Here's how it should flow:

Step 1: Reduce Raw Materials

When the manufacturing run happens, reduce your IMS and accounting records:

- Packaging: 20,000 → 15,000 units (consumed 5,000)

- Labels: 15,000 → 10,000 units (consumed 5,000)

- Powder: 80 kg → 70 kg (consumed 10 kg)

Your Raw Materials balance drops from $16,400 to $12,200. That's $4,200 worth of your raw materials that went into the finished goods.

Step 2: Estimate the Co-Manufacturer's Costs

You estimate they'll charge you $33,300 for their ingredients and labor ($6.60 per unit × 5,000 units).

Since you don't have the invoice yet, you create a Goods Received Not Invoiced (GRNI) account:

- Book $37,500 to Finished Goods inventory ($4,200 raw materials + $33,300 estimated co-man costs)

- Book $33,300 to GRNI (a liability account)

Step 3: When the Invoice Arrives, Adjust

Two weeks later, the co-manufacturer's invoice arrives. Let's say it's $35,000 instead of $33,300.

You reverse the GRNI estimate ($33,300) and book the actual invoice ($35,000) to Accounts Payable. Then you adjust your Finished Goods inventory by the $1,700 difference.

If you've already sold some of the inventory (just like in Mistake #5), you split the adjustment between what's on hand and what's been sold.

Why This Matters

If you're not tracking the consumption of raw materials and the creation of finished goods in real time, your inventory balances are wrong.

You're showing too much in raw materials and too little (or nothing) in finished goods. Your COGS is wrong. Your gross margins are wrong.

And if you're working with multiple SKUs, multiple production runs, and multiple co-manufacturers? The errors compound fast.

You end up with a giant mess at year-end where you're trying to reconcile thousands of units of raw materials that should have been consumed months ago, and finished goods that you've been selling at incorrect COGS the entire time.

The key is treating the co-manufacturing process the same way you treat every other step: estimate costs before invoices arrive, track the flow in both systems, and adjust when actual bills come in.

Mistake #8: Losing Track of Inventory in Transit Between Locations

You've got 5,000 units of finished goods sitting at your main 3PL in New Jersey. Business is going well. You decide to start selling on Amazon, so you need to send 2,500 units to Amazon FBA.

You create a shipment plan, the 3PL loads it onto a truck, and it's on its way to Amazon's fulfillment center.

So here's the question: Where is that inventory right now?

It's not at your New Jersey 3PL anymore—they already deducted it from their inventory count when they shipped it out.

It's not at Amazon yet—they haven't received it and checked it in.

It's somewhere on I-95 in a truck.

But when you go to reconcile your inventory, what do you see?

In your IMS:

- New Jersey 3PL: 2,500 units

- Amazon FBA: 0 units

- Total: 2,500 units

In your accounting software:

- Finished Goods: $37,500 (5,000 units at $7.50 each)

Your accounting software says you have $37,500 worth of inventory (5,000 units). But your IMS only shows 2,500 units across all locations.

So where did the other 2,500 units go?

The Problem: Your IMS Can't Track In-Transit Inventory Between Locations

A lot of inventory management systems can track goods in transit from your supplier to your warehouse. But not all of them can handle goods in transit between your own locations.

So when you ship from your 3PL to Amazon, the units disappear from one location but don't appear at the other for 3-7 days. And during that window, they're just... gone. Unaccounted for.

If you're reconciling your IMS against your 3PL dashboards, you're going to see a discrepancy. Your 3PL says they have 2,500 units. Amazon says they have 0. That's 2,500 units. But your accounting says you should have 5,000.

Cue the panic: "Did we lose a shipment? Did someone steal inventory? Is the 3PL's count wrong?"

No. The inventory is fine. It's just in transit.

The Right Way: Track In-Transit Status (If Your IMS Allows It)

If your IMS can handle it, create a "goods in transit" status for inventory moving between locations:

- New Jersey 3PL: 2,500 units (on hand)

- In Transit to Amazon: 2,500 units

- Amazon FBA: 0 units

- Total: 5,000 units ✓

Now your IMS total matches your accounting total.

On the accounting side, you don't actually need to do anything. Your Finished Goods balance stays at $37,500 regardless of whether the inventory is at Location A, Location B, or in a truck between them. The total value doesn't change just because it's moving.

If your IMS can't track in-transit inventory:

At minimum, keep a manual log or spreadsheet:

- Date shipped

- Units shipped

- From location → To location

- Expected arrival date

This way, when you're reconciling and you see a 2,500-unit discrepancy, you can check your log and say, "Oh right, that's the shipment to Amazon that left on Monday. It'll show up in their system by Thursday."

Why This Matters

If you're not tracking in-transit inventory between locations, you're going to have constant reconciliation issues.

Every time you ship between warehouses, there's going to be a multi-day gap where the inventory "disappears" from your system. And if you're shipping frequently (weekly transfers to Amazon, moving inventory between 3PLs, consolidating to a new warehouse), those gaps start overlapping.

Suddenly you're looking at discrepancies of thousands of units that you can't explain. You don't know if it's:

- Inventory loss

- 3PL counting errors

- System errors

- Or just... stuff in trucks

And if you can't trust your inventory counts, you can't forecast properly, you can't make purchasing decisions confidently, and you're constantly second-guessing whether your numbers are real.

Tracking in-transit status—even manually—closes that gap and gives you visibility into where every unit actually is at any given time.

Mistake #9: Never Doing Physical Counts

Let's say you've been following all the best practices. You're tracking deposits properly. You're capitalizing landed costs. You're doing three-way matches. You're estimating GRNI. Your systems are synced.

And yet, six months later, something still feels off.

Your IMS says you have 5,000 units of your best-selling SKU. Your accounting software matches. Everything looks good on paper.

So you call your 3PL and ask them to do a physical count.

They count. They recount. They send you the report.

4,500 units.

You're missing 500 units. That's $3,750 worth of inventory that's just... gone.

Where did it go?

The Reality: Systems Drift

Here's the thing: Even with perfect processes, your systems drift over time.

- Your 3PL's warehouse staff miscounts during receiving and logs 100 units when they actually received 95.

- A pallet gets damaged and someone throws it out without telling you.

- Units get stolen (yes, it happens).

- Your 3PL "borrows" some of your inventory to fulfill another client's order and forgets to log it.

- A software glitch double-counts a shipment.

- Someone fat-fingers an entry and types 1,000 instead of 100.

None of these are because you're doing something wrong. They're just the reality of operating a supply chain with multiple systems, multiple people, and multiple points of potential error.

And if you're not doing periodic physical counts, you have no way of catching these discrepancies before they compound.

What Should Happen

At minimum, you should be doing physical counts:

Quarterly for fast-moving SKUs (your top 20% of products by revenue)

Annually for everything else

Immediately when something feels off (system discrepancies, unexpected stockouts, etc.)

When you do a physical count:

- Compare the physical count to your IMS

- IMS says 5,000 units

- Physical count says 4,500 units

- Discrepancy: 500 units

- Investigate if the discrepancy is material

- Is there inventory in transit that wasn't accounted for?

- Was there a recent shipment that hasn't been logged yet?

- Is there a pending adjustment you forgot to make?

- Adjust your systems to match reality

- If you can't find the 500 units, you need to write them off

- Reduce your IMS from 5,000 to 4,500 units

- Reduce your inventory value in your accounting software by $3,750

- Book the $3,750 to COGS (Shrinkage or Inventory Adjustment line)

It's not fun. You're essentially saying, "We lost $3,750 worth of inventory and we don't know why." But here's the alternative:

You don't do a physical count. You keep operating on the assumption that you have 5,000 units. You make purchasing decisions based on that number. You forecast inventory levels based on that number.

Then one day, a customer places a large order for 1,000 units. You check your IMS—plenty of stock, no problem. You accept the order.

Your 3PL goes to fulfill it... and realizes you only have 4,500 units total. You can't fulfill the order. You lose the customer. You lose revenue. And you still have to figure out where the 500 units went.

Why This Matters

Physical counts are the safety net that catches all the other mistakes.

Missed a three-way match? Physical count will reveal it.

Forgot to adjust for damaged goods? Physical count will catch it.

Co-manufacturer invoice was wrong and you didn't split the adjustment correctly? Physical count will show the discrepancy.

3PL miscounted during receiving six months ago? Physical count surfaces it.

This is not glamorous work. It's tedious, time-consuming, and often reveals problems you'd rather not deal with.

But it's the only way to know—with certainty—that the numbers in your systems actually match the inventory sitting on shelves in your warehouse.

And if you're making decisions based on those numbers (which you are), you need to know they're real.

The Common Thread

If you made it this far, you've probably noticed a pattern:

Every single one of these mistakes comes down to the same core issue: things happen at different times, in different systems, and most people don't bridge the gap.

- You pay a deposit, but inventory doesn't exist yet → wrong account

- Goods ship, but they're not received yet → wrong status

- Freight bills arrive late, but the cost is real now → wrong timing

- Invoices arrive after you've sold the inventory → wrong allocation

- Inventory moves between locations, but systems don't sync → wrong visibility

And when you don't bridge those gaps? Cash disappears. COGS is wrong. Margins are inflated. And you're making multi-thousand dollar decisions based on numbers that don't reflect reality.

The good news: None of these are complicated fixes. They just require understanding when things happen, where they should be recorded, and how the information flows between your IMS and your accounting software.

Get that right, and the numbers start making sense.

Ignore it, and you'll keep wondering where your cash went and why your inventory balance never seems to match what your 3PL actually has on hand.

Do You Need a Lie Detector for Your Numbers?

Look, we get it. You started a brand to sell products, not to become an expert in inventory accounting arcana.

But here's the thing: if your QuickBooks says one thing, your IMS says another, and your 3PL is giving you a third number, somebody's lying.

Or more accurately, everybody's telling their version of the truth and nobody's speaking the same language.

That's where we come in.

At UpCounting, we work with e-commerce brands that have overseas supply chains—the ones dealing with deposits, freight forwarders, co-manufacturers, and all the messy in-between steps that make inventory accounting feel like you're playing telephone across three continents.

We don't just clean up your books. We make sure your systems actually talk to each other.

We reconcile your IMS to your accounting software. We track goods in transit. We capitalize landed costs. We do the three-way matches.

Basically, all the stuff you just read about? That's our Tuesday.

And no, Dom Toretto probably won't steal your shipment. But if he does, we'll at least make sure you book it correctly.

Schedule a call and let's figure out what your numbers are actually trying to tell you.

.jpg)